Grounded Whirling

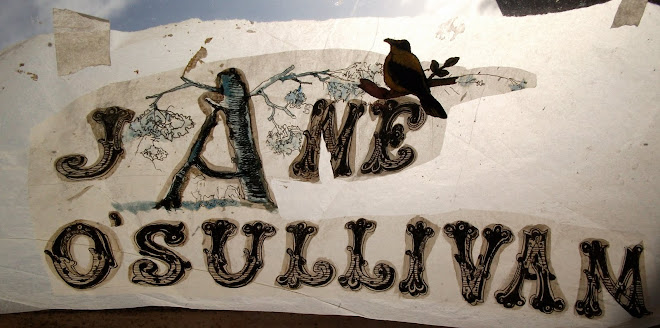

Jane O’Sullivan, Grounded Whirling

By: Jenny Walton

Jenny Walton was a curatorial intern at Talbot Gallery & Studios during Jane O’Sullivan’s exhibition ‘Life is Supported in Mysterious Ways’, July 2014.

All quotes are from conversations with the artist.

“I make a framework for myself to work within/against as a starting point, as a way into my subject matter, a meaning that I create from the many disparate sources that inspire my finished work, but these "dispirations" although valuable and ephemeral (as I believe life to be) are not the work , the work must become itself”.

There was an ‘ease of presence’ with the exhibition Life is Supported in Mysterious Ways and this viewer was able to feel her own affiliation with the particular objects Jane O’Sullivan has chosen to find and the works into which she has incorporated them. O’Sullivan speaks of spaces as poetic. To me, through tactile work which emphasises its materiality, an intangible place of contemplation was offered in each piece through which to consider all of the work, which is in a myriad of media. Like the subtle threads (such an understated and integral material in most of O’Sullivan’s pieces) which feature in The Forest of Solitude, all the works in Life is Supported in Mysterious Ways were linked over one body and on its tangents. This is one of the ways in which the exhibition at Talbot Gallery provided the pieces in Jane O’Sullivan’s solo exhibition as individual pieces and as a coherent, self-supported body of work.

The film piece, Searching for the Land of Shuniya is shown mounted in an adapted box (the screen visible through an open rectangle) which hides a text written in blue crayon “I come to thee laden with gifts” and a small painted sketch of a tree. This small film piece, intimately peered at through its frame, with accompanying track on equally intimate headphones lasts just over three minutes and contains many visual elements and themes explored in the cloth and clay pieces in the rest of the room.

The sound of buffeting wind (at 0:22) is incorporated into the music track by Barry Johnston. The music, like the visuals of Searching for the Land of Shuniya is mysterious and floating. The clear, rapid higher notes and sliding string dissonances are grounded in a soft, gently throbbing bass. The use of both sonic and visual collage is enticing. It indicates the multiple representations each object or material can hold for O’Sullivan and also introduces us to the use of repeated patterns throughout her work. Even the subtle, highly effective buffeting wind can be felt, by this viewer, articulated in the delicate stoneware, swallow’s nest piece sing yourself whole again. The title, composition and presentation of sing yourself whole again (the shelf for this fragile, weighted piece is a patterned, antique handkerchief box) combine in the same gentle but determined manner to articulate O’Sullivan’s interest in the ethereal (in these cases sonic) as material and consequential.

In the film, Shuniya’s point of stillness is sought through a loose cyclical narrative, whirling around delicately and slowly upon itself. The film moves in swirls of theme from air to water to earth and back again. O’Sullivan’s juxtaposition of a delicate, personal, intricate ‘man’-made (lace, print pattern, cameo) onto nature (Irish bogscape, lake, swan) is subtly jarring, similar to its accompanying track. The beginning and end of the film (the cameo figure) is made using stop-motion animation. These 12 seconds of the work, the narrative and the music are all simultaneously precise and meandering; specific in their looseness.

The figure featured in the work plays with her own figure / ground relationship; first appearing wrapped on herself as part of that ground. Her next appearance is floating across the screen in a vertical position holding a branch aloft. Her position (lying flat) is complicated by her positioning (floating) which, at eye level in the video on the wall, is implied as being above the viewer. Thus, the positions of the viewer’s gaze are shifting and have the effect of identifying the figure as just one element of this work, rather than its principle focus. Another version shows us a head-bowed, cruciform position and yet another, (the side-view of a similar position this time with head and arms arched back) changes the vantage point of something very visually familiar on its side, presenting the viewer with its equally flat and graphic image but using flatness and colour and figure and ground - collage, rather than illusionistic contraposto. O’Sullivan speaks of this figure as “the floating figure, Ostara, the self, the collector”, all figures that are further explored both individually and in conversation throughout the exhibition. These are figures that are presented as definitions of the self and other within one. “She, to me, is part of us all; she can represent the potential in the floating woman’s existence”.

Like the floating figure, the swan is an insertion into the landscape of the film. The swan, in its sharp definition, poses a counter to the patterning in Searching for the Land of Shuniya. Pattern and repetition; of the lace, of the bog cotton, of the print material are played against the swan who is presented in sharper contrast, bold and committed on the small screen. While the floating figure explores her many configurations, the figure with the ability to fly chooses not to. The swan does not serve to assign the other elements to frivolity however, quite the opposite. Its presence brings strength, tangibility and a commitment to being rooted-to-the-earth (water) to all of the other features of the film piece. To me, O’Sullivan seeks for her work to perform this swan-task, to root her manifold ideas in a delicate, strong manner, presentable to a viewer.

The handmade glass slides, which consist of images from the artist’s book Holding a Space and film stills from Searching for the Land of Shuniya, in their delicate ethereality, are some of the most dense works in the exhibition. The lack of linearity (removal from the film) intensifies specific images and overlays from the film, bringing to light both their delicate visual nature and their confusing, juxtaposed existence. Initially, these 12 plates appeared to have been less ‘tampered-with’ than their companions in the room. However, hung on specially built shelves with carefully taped edges they evidenced, in a similar way to the boxed-in video, O’Sullivan’s need to be materially involved in all that she does.

Predominantly the slides depict the swan and the ‘floating figure’, the figurative elements of O’Sullivan’s book and film. However, the inclusion of some landscape slides and the complication of most of the slide images with overlays indicate O’Sullivan’s interest in the movement, the continuing life of both the objects she finds and her completed works. This gentle emphasis on the transient, this highlighting of the moment of movement between, is about both the fascination with and potential for her new exploration of film making and her intent for these found and made art objects. In this way it follows that the figurative slides (indexes of the artist and her practice) make both material and ethereal O’Sullivan’s processes and conclusions in art making. The interest in transparency and transience of the object can also be seen in dwelling in the realms of possibility vol. 1-9, a found book page altered with a marker drawing of a woman who, in holding both hands aloft, looks as though she is both waving and attempting to escape. The page is presented in an antique wooden standing frame, open at the top, between panes of glass. The figure appears to be retreating within her reflective glass case but, interestingly, doesn’t appear to be surrendering.

This need to be close to her work, to physically work out the “poetic spaces” of these artworks she discusses, is newly evident in O’Sullivan’s recent development into the making of clay pieces, both to insert in the “found-object” world (as is evident in The Forest of Solitude) and to display as their own entities. The amalgamation of collected objects and white ceramic stone sculpture which form a passionate silence fit one another perfectly and the uncanny nature of this piece is brought about by how ordered, layered and encased it is. O’Sullivan’s display case is subtly inverted. The threading of the paper rose through the clay looks vulnerable, the damask fabric cloth is displayed seam-side up and, despite being layered upon both this fabric and the transfer ware plate, the headless figure, the dress, seems so directly moulded from the clay, from the earth as if nothing were between it and the ground. the collector of calm provides possible interpretation for the uncanny in the clay works, showing the earth-bound, of earth made, figure in both lying (sleeping) position and upright, out-of-body state. Being rooted to its reflection on the gilt mirror tray and surrounded by its sibling, the swan’s, feathers, the collector (one of O’Sullivan’s selves as other / other as self) again evokes earth and water and air and the possibilities for all three within a material and ethereal world and within the artist’s practice.

I don’t impose this of-the-earth relation to clay upon Jane O’Sullivan’s work and it is something we have discussed. To me it emphasises her relationship to all of the materials and objects she uses in her practice as found objects. Her pieces on material are ‘drawn collages’ of found image and text and reflect O’Sullivan’s need to combine in order to create the work of art. The found objects, images and text are never just that, found, they are modified and incorporated, catalysts for artworks, rather than entirely the artwork themselves. In treating the images and texts in this way O’Sullivan seeks to remove them from an original meaning and make each become something not so obvious. This process takes time and is her practice. “I hope for it to be more open ended, more generous and mysterious.” The generosity and mystery offered by the found object, image, text are the conduits for connection between artist and the viewer and between the various entities of self which O’Sullivan seeks to explore.

The intent gazes of these entities operate through the drawn works in Life is Supported in Mysterious Ways, particularly those on antique fabric (predominantly drawings of female faces with some text either drawn or typed). The figurative positioning in Searching for the Land of Shuniya has been beautifully adapted from, and feels intrinsically linked to, the figures of Ostara in Ostara and her Deer and Ostara and her Swan, drawings made on the insides of antique book covers, framed by the material folded from the outer binding of the books. In Ostara and her Deer, the figure of Ostara (seen also in the collector of calm), curls below the deer, echoing the form of the animal, both of them staring intently in different directions. Her gaze directs us out of the book’s frame to the ground. In Ostara and her Swan, Ostara’s position is swapped to the upper register created by the broken book binding. In this instance she is rooted to the lower register by a drawn thread to her swan. Again, they look very intently in different directions. When viewed together, as they were presented in Talbot Gallery, each figure seems intent on fully occupying but also engaging beyond its page. Of the four, the deer is the only figure whose gaze directly engages with the viewer, but all four seek out the space beyond the book.

Originally amalgamated from many garments of antique and modern fabrics to fit a particular theatrical costume need, the found object in (i am enough) is embroidered with the sketch outline of the words – “I am enough”. The embroidery hoop is left in the garment, marking a spot, a (w)hole. It created, in this exhibition, a tunnel-like focal point at the end wall. The piece is so totally itself in its incompleteness it is breathtaking. Here the thread is bold and various. The stitched words, though tentative and ‘sketched’, are definitive and grounded. (i am enough) presents preparatory work as complete not in the manner of a work-in-progress (a behind-the-scenes look at the artist’s practice) but based more on the notion of the preparatory work as complete thought; as complete as it can be for now. The threads of the dress (its parts, its lace, its composition) are from many origins and now include O’Sulllivan’s own blue thread; and the work has already lived numerous further lives with O’Sullivan. Originally she hung and photographed it in the widow of the Berlin apartment where she was staying when she found it, typically exploring all the angles the new object was presenting to her practice.

It is through (I am enough) that another dimension to what Jane O'Sullivan did at Talbot Gallery opens up. The meticulousness with which each piece and each detail had been selected for inclusion; the personal, hand-editing of film; the selection of image and material over and over and over again in insistence of their consideration, in the presentation of a personal and artistic point of view, is O’Sullivan’s assertion to Hold a Space. In (i am enough) the effect of this is both thorough and empty at once. As a culmination to the exhibition it released the clutter and material intensity of the other work to free a space for the viewer to hold. O’Sullivan’s insistence is not that we agree with her but that her work be a catalyst for the viewer’s own consideration of the space each may hold, either within the context of the gallery space, the exhibition or beyond.